Most leadership teams don’t suffer from a lack of logistics data. They suffer from a lack of decision ready insights.

You may know where containers are, which trucks are late, and which distribution center is backed up. Yet the response still looks familiar: expediting, overtime, buffer inventory, manual replanning, escalation calls, and operational heroics.

This is the first article in a four-part series on logistics digital twins, how they move logistics from visibility to control, why the hub is the logical starting point, and how to scale from hub twins to enterprise orchestration.

Why this series now

Four forces are converging:

1) Cost-to-serve is under pressure in places leaders don’t always see

Detention, premium freight, missed cutoffs, overtime volatility, rework, and buffer inventory can look like “operational noise.” At scale, they shape margin and working capital far more than most planning discussions acknowledge.

2) Service expectations are rising while tolerance for buffers is shrinking

Customers expect tighter and more reliable delivery promises. Meanwhile, the classic insurance policies, extra inventory, spare capacity, and manual intervention—have become expensive.

3) Volatility has become structural

Congestion, weather events, labour constraints, and capacity swings are no longer exceptions. In many networks they are the baseline, they ripple across modes and hubs faster than traditional weekly planning cycles can absorb.

4) Sustainability is moving from reporting to operations

The biggest emission levers in logistics are operational: waiting vs flowing, routing, mode selection, idling, rehandling, and expediting. You cannot manage carbon seriously without managing variability seriously.

The value of logistics digital twins

Service reliability. A logistics digital twin improves the credibility of your promises by continuously reconciling plan versus reality. Instead of relying on averages, it helps you anticipate bottlenecks and protect cutoffs, so customer commitments become more stable and exceptions become less frequent.

Cost-to-serve and productivity. Twins reduce the hidden costs of variability: queues, idling, rework, overtime spikes, and premium transport decisions made under pressure. Over time, they turn constrained assets, labour, docks, cranes, yards, into capacity you can actually plan against.

Resilience. A twin gives you a repeatable way to respond to disruptions. You can test scenarios, predefine playbooks, and replan faster, reducing reliance on ad-hoc escalation and individual heroics.

Sustainability. By reducing waiting, unnecessary speed-ups, and expediting, twins cut emissions where it matters most—inside day-to-day operations. Just as importantly, they make trade-offs explicit: service vs cost vs carbon, supported by data rather than intuition.

What a logistics digital twin is

A logistics digital twin is a closed-loop system that links real-time logistics events to prediction, simulation, and optimization, so decisions improve continuously across hubs, flows, and the wider network.

What it isn’t:

- A 3D visualization

- A dashboard-only control tower

- A big-bang model of everything

If the twin doesn’t change decisions, it’s not a twin. It’s reporting.

Where the technology stands today

Mature and accelerating. The foundational building blocks are now broadly available: event streaming from operational systems, predictive models for ETAs and handling-time variability, simulation to stress-test plans, and optimization to sequence scarce resources. AI is also improving the speed and quality of replanning, especially in exception handling and dynamic decision support.

Still hard (and why programs stall). The toughest challenges are cross-party data access and identity matching, proving models are decision-grade, and getting decision rights and operating rhythms clear. In practice, governance of decisions matters as much as governance of data.

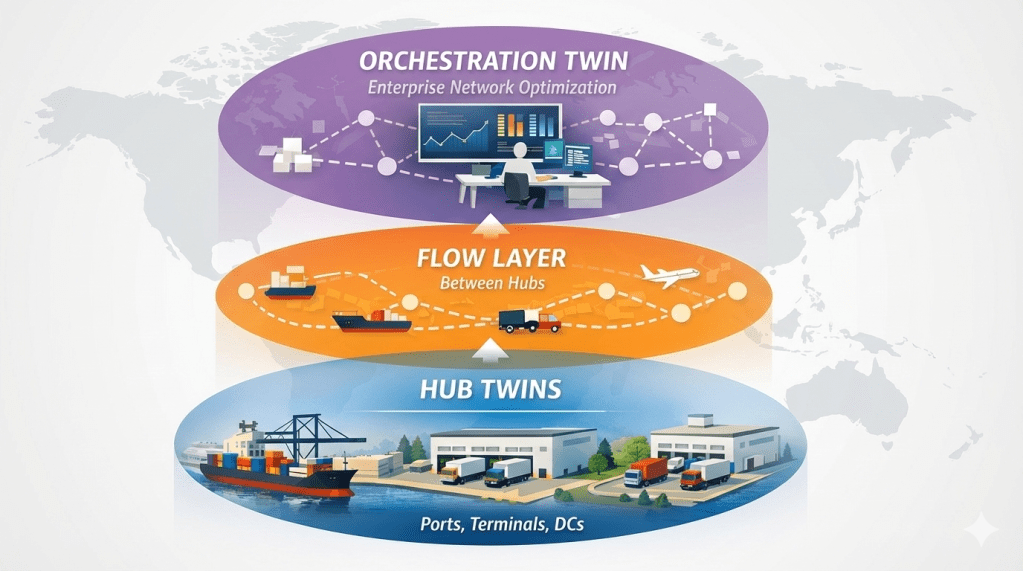

The three layers of logistics digital twins

- Hub twins: ports, terminals, DCs; manage capacity, queues, sequencing, labor and equipment.

- Flow layer: between hubs; manage ETA variability, corridor constraints, routing under disruption.

- Orchestration twin: across the network; manage allocation, promise logic, mode switching, scenarios, and network design choices.

This series starts at the hub for a reason.

Why it’s logical to start at the hub level

When companies say “we want an end-to-end digital twin,” they usually mean well and then get stuck.

The fastest path to value is to begin at the hub level because hubs offer four advantages:

1) You can control outcomes. Hubs have clear operational levers: sequencing, scheduling, prioritization, and resource deployment. When those decisions improve, results show up quickly in throughput, dwell time, and service reliability.

2) Data is more attainable. Hub data typically sits in a smaller number of systems with clearer ownership. That is a far easier starting point than cross-company, end-to-end integration.

3) Hub wins compound across the network. A reliable hub stabilizes upstream and downstream. If arrivals are smoother and throughput is predictable, you reduce knock-on effects across transport legs.

4) Orchestration depends on commitments, not guesses. Enterprise orchestration only works if hubs provide credible capacity and timing commitments. Otherwise the network plan is built on wishful thinking.

If you remember one line from this article, make it this: If you can’t predict and control your hubs, your network twin will only automate bad assumptions.

The minimum viable twin (how to start without boiling the ocean)

A minimum viable logistics digital twin has five ingredients:

- A short list of critical events you can capture reliably

- A state model that represents capacity, queues, backlog, and resources

- A decision loop with a replanning cadence and exception triggers

- Clear decision rights: who can override what, and when

- Two or three KPIs leadership will sponsor and use consistently

The most reliable way to get traction is to pick one flagship hub use case and scale from there.

In the next two articles, we’ll look at two examples: sea freight and ports (high constraints, many actors), and road transport and warehouses (high frequency, direct cost-to-serve impact). We’ll close with orchestration and network design—where “run” data replaces assumed averages.