Sea freight has an expensive habit: sprint-and-wait.

Vessels speed up to “make the window,” arrive early, and then sit at anchor because the berth plan isn’t ready—or because constraints inside the system (yard, cranes, labor, landside congestion) shifted while the vessel was still at sea. That’s the visible symptom. The root issue is broader: a lack of synchronization across voyage decisions, port-call coordination, terminal capacity, and cargo flow.

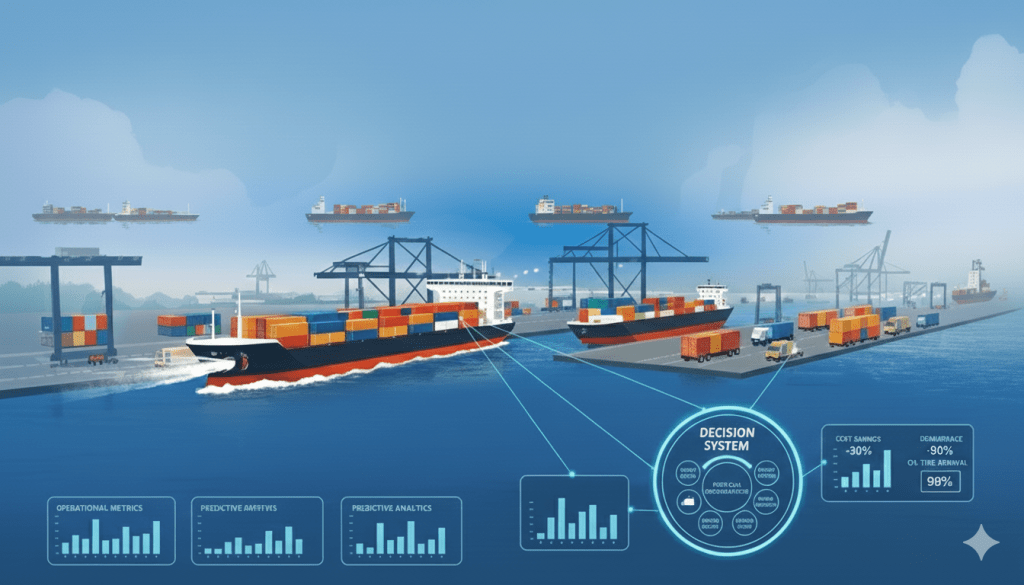

A sea/port logistics digital twin earns its place when it becomes a decision system, continuously reconciling plan versus reality so ship and port decisions converge on a realistic plan.

The prize: operational cost down, penalties down, efficiency and flow up

Lower fuel cost and better vessel utilization. Timing is the biggest controllable lever at sea. Credible arrival windows reduce unnecessary speed-ups and idle time and avoid schedule slippage that quietly erodes utilization and network reliability.

Reduced demurrage and detention. Demurrage and detention are often accepted as inevitable. They are a synchronization failure cost. Missed cut-offs, late readiness signals, or pickup plans that do not reflect yard reality can cascade into days of detention across hundreds of shipments.

Better schedule reliability. When port-call plans and terminal readiness become trustworthy, downstream planning stabilizes: rail windows, truck appointments, warehouse waves, and customer commitments. Less variability means less expediting and less buffer inventory.

Higher terminal productivity under uncertainty. Berth, cranes, and yard moves are expensive constraints. A twin does not create capacity; it helps you use existing capacity with fewer bottlenecks, especially when reality deviates from plan.

Decision loops of “total sea freight optimization”

1. Voyage & arrival optimization

The twin shifts the objective from “arrive early” to “arrive when the system is ready.” It updates the feasible arrival window using live signals (constraints, congestion, readiness, service-time uncertainty) and turns that into speed-profile decisions. It also clarifies where to carry buffer: buffer at sea is often cheaper than buffer as yard congestion, missed connections, or rushed recovery actions. The output is an arrival commitment with confidence, not a best-guess ETA.

2. Port-call orchestration

Port calls involve carriers, terminals, port authorities, pilots, towage, agents, and connections. Coordination often fails because each party works from a slightly different data set / ”truth”. The twin creates an event-driven insight; planned vs actual milestones are visible early, conflicts surface sooner, and replanning becomes a cadence rather than a firefight.

This is also the natural place to start sharing cross-party data. The port call is where you can bridge “ship truth” and “terminal truth” into a single version of truth for decisions: one set of milestones, one set of readiness signals, and one shared view of what changed and what it implies.

3. Terminal capacity optimization

The twin supports berth allocation, crane assignment, and yard sequencing under uncertainty, so congestion does not spiral. The differentiator is speed of response. It is designed to replan fast when reality changes (late arrivals, outages, weather stops, landside surges). Small plan changes early can prevent large productivity collapses later.

4. Stowage and loading planning integrated with execution

Stowage determines the loading/discharge sequence, impacts crane productivity, and drives yard retrieval patterns. The twin connects stowage to execution constraints: stability, port rotation, weight distribution, and segregation rules (cargo that must not be stowed close together). When stowage and yard retrieval are misaligned, rehandles and last-minute reshuffles rise, destroying productivity and increasing the risk of missed pickup windows that feed demurrage and detention.

5. Address specific constraints

For instance, in liquid and hazardous logistics, there’s an additional constraint that often impacts reality: readiness. If tanks or compartments aren’t clean, inspected, and certified, capacity exists on paper but not in practice. A practical twin treats “tank readiness” (cleaning / maintenance / certification status) as a first-class constraint alongside berth and terminal capacity, with lead-time visibility so cleaning crews and inspectors can be scheduled before the vessel arrives, not discovered as a problem at the berth.

Example: a disruption day where the twin pays for itself

A vessel announces a 12-hour delay overnight. Without synchronization, the berth plan, crane plan, and yard retrieval continue as if nothing changed, until congestion builds, the berth window turns into a conflict, and shipments miss gates, triggering demurrage and detention exposure.

In a twin-driven setup, the delay triggers an immediate replan: the arrival commitment is recalculated with a confidence band, port-call milestones become the shared single version of truth, berth/crane priorities are reshaped to avoid an unmanageable peak, and the loading sequence is updated with constraint checks so yard retrieval matches the revised plan. The result is fewer hours at anchor, fewer recovery speed-ups, fewer exceptions, and lower downstream cost.

Minimum viable architecture

- Event backbone: shared milestones and exceptions (arrival, readiness, service start/finish, berth changes).

- State model: constraints and queues (berth, cranes, yard capacity, container readiness and (tank) readiness, plus landside congestion).

- Decision engines: prediction + simulation + optimization (sequencing and stowage/execution alignment).

- Control loop: rolling replans plus event-triggered replans with clear authority.

How to implement without boiling the ocean

- Make events decision ready. Standardize a minimal set of milestones and capture them reliably.

- Win at the port call/hub. Planned-vs-actual discipline, early conflict detection, and a clear replanning cadence.

- Optimize terminal decisions under uncertainty. Berth/crane/yard sequencing plus simulation for “what if.”

- Connect stowage with execution. Constraint-aware stowage aligned with yard retrieval and crane sequence and, where relevant, tank readiness.

- Export commitments to the network. The output is commitments with confidence as inputs for enterprise orchestration.

The questions executives should ask to govern the system

- Who owns arrival and berth commitments, and who can override them?

- What is the replanning rhythm, and what triggers exceptions?

- Which objective wins in conflict: productivity, reliability, fuel/emissions, safety, or penalty avoidance?

- Do our contracts and incentives reward synchronization, or do they still reward sprinting to a congested berth and shifting cost downstream?

- What do we automate vs recommend, and what evidence is required to increase automation safely?

What’s next

Part 3 moves to road transport and warehouses—a higher-frequency world where variability is constant, labor availability is often the binding constraint, and cost-to-serve impact shows up immediately. Part 4 connects it all: orchestration and network design, where run data replaces assumed averages.